Satellite images play major role in building sustainable soy supply chain

To create a supply chain free from deforestation, information is key. And when it comes to soy, that means understanding what is happening on the ground, both the big picture and the small details at every step along the way.

But watching areas that cover millions of square kilometers is not a desk job. In fact, it is best done from space.

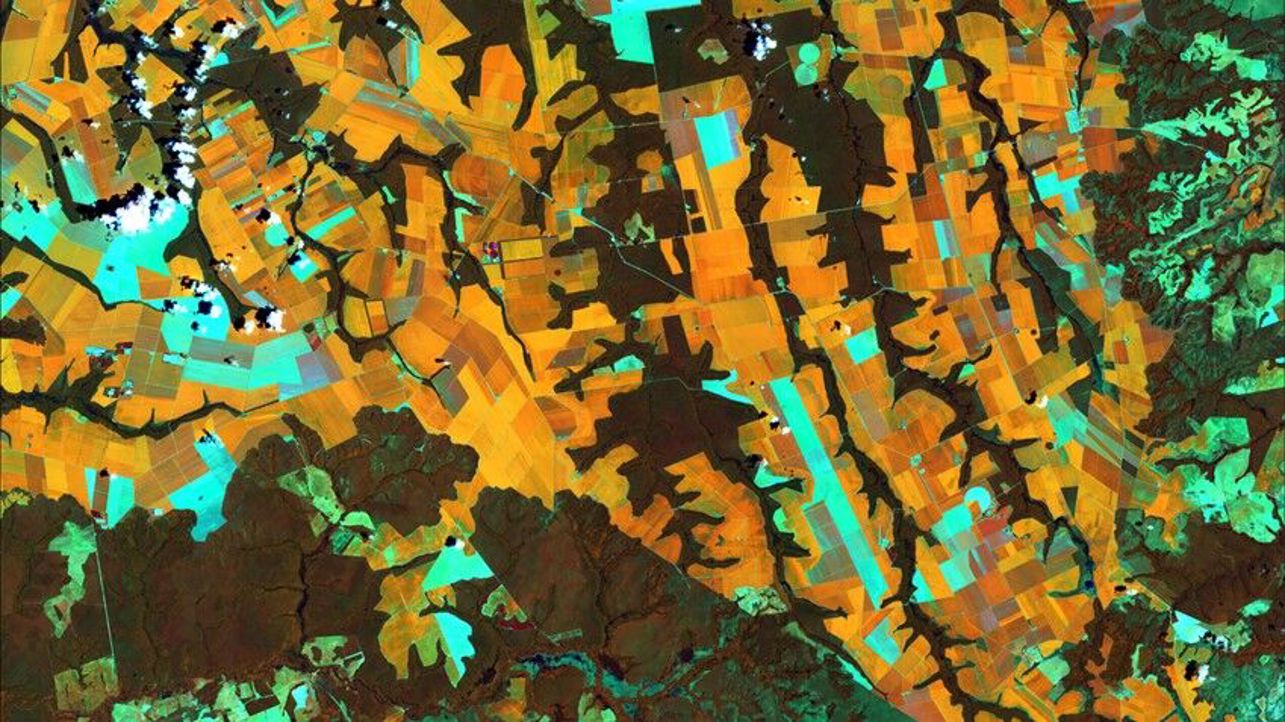

That’s why COFCO International partners in Brazil with Agrosatélite, a company that uses remote sensing satellite images to observe the Earth’s surface and possible impact of soy cultivation on the country’s most valuable ecosystems.

These images can monitor dynamic targets such as annual crops and also land cover changes linked to deforestation.

SIMFaz, Agrosatélite’s farm monitoring system helps assess environmental, social and financial risks. The technology supports COFCO International’s joint project with the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) to develop a more traceable and sustainable supply chain in the Cerrado’s Matopiba region, an important biodiversity hotspot.

The aim is to ensure that supplying farms are free of forced labor, are not located on indigenous land, conservation units or embargoed areas, and are in compliance with local regulations as well as global agreements. The project is expected to cover at least 85 percent of COFCO International Brazil’s direct suppliers in the Matopiba region by 2021, and to fully cover the region by 2022 the latest.

“Achieving a deforestation-free soy supply chain requires concerted effort by all the players involved,” says Wei Peng, Head of Sustainability for COFCO International.

“But we need accurate information and data to make the right sourcing decisions. We are in a much better position to do that when we have this satellite imagery and interpretation.”

Mesmerising images

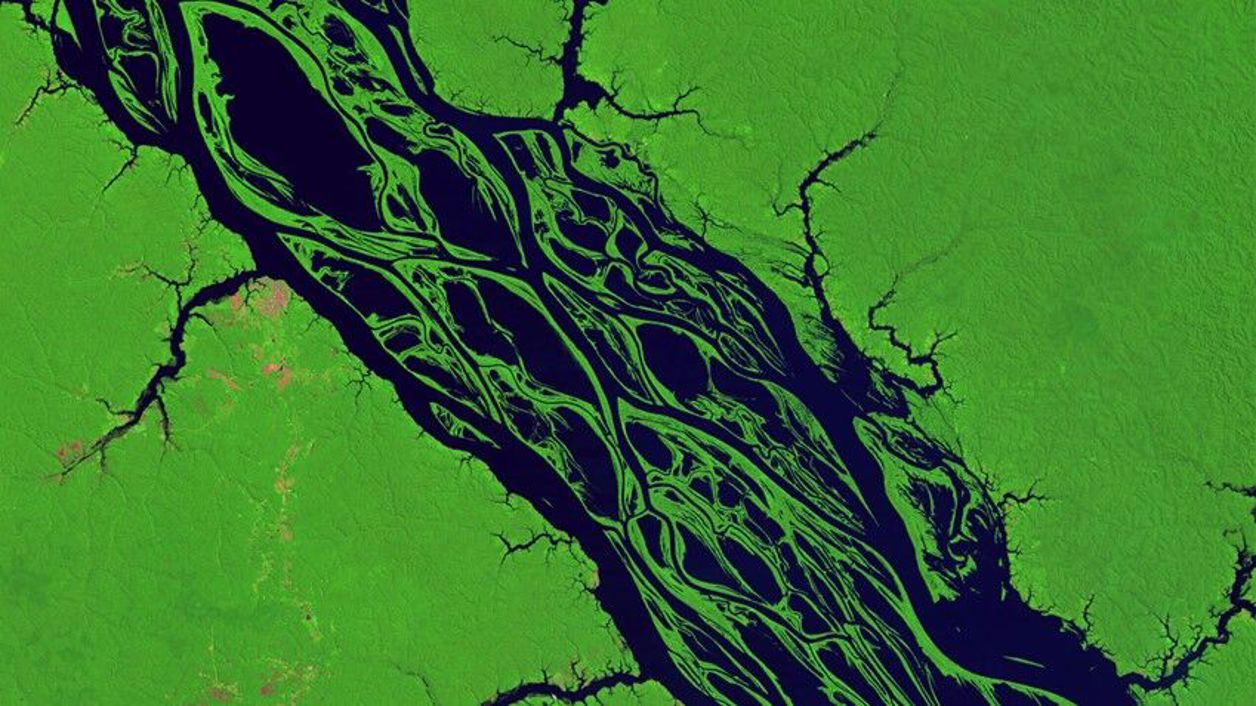

Satellite imaging is not new. In July 1972 Landsat-1 was launched with the intent to study and monitor our planet’s landmasses.

A few months later, the crew of Apollo 17 mesmerised people around the world when it photographed the Blue Marble, an image of the earth taken from a distance of about 45,000 km.

What has changed since then and why have satellite images not been used more effectively for conservation purposes much earlier?

Bernardo Rudorff, the CEO and co-founder of Agrosatélite, says the biggest advances in satellite imagery are the revisit frequency at which the images are taken and our ability to interpret and subsequently act on them.

“The pictures back in the seventies have certainly captured our collective imagination,” says Rudorff, who has worked as both photographer and agronomist. “But as the images became more sophisticated and more frequent, we began to use them to better understand the extent of human impact on the planet.”

Automatic image classification to produce high quality soy maps still has some limitations, but is improving fast thanks to the availability of more and more images during the short period of the soy growing season.

Technological advances mean that satellite images are better able to monitor our planet’s surface at different spectral, temporal and spatial resolutions than ever before. But the process of extracting the information often requires specialised teams to be involved.

That’s why Agrosatélite’s people frequently participate in field visits. In this way, they can stay up to date with different local and regional differences as well as with variations related to climate or economy.

Technology is not enough

So can satellite images save the forests? According to Rudorff, yes, but only if there is a concerted effort to act on what we see.

“For sure it can!,” he says. “Without technology, we would not know the pace of deforestation in critical regions and nothing would be done to halt it.”

The Soy Moratorium, for example, a zero-deforestation initiative for the soy production chain, is only possible using satellite-based technology to detect soy that has been planted on deforested land since July 22nd 2008.

But technology by itself is not enough.

It needs to be complemented with strict policies and actions. It also requires the buy-in of all players along the soy supply chain, especially the producers themselves.

A viable and long-term solution to end soy-driven land conversion should involve the entire industry, and, most importantly, should put producers at the heart of the transition. COFCO International is working towards such a solution as part of various international groups.

COFCO International now wants to extend its use of satellite imagery to cover more supplying farms located in other sensitive regions in order to understand the land use and land cover changes associated to soy expansion.

“Soy production can go hand in hand with the conservation of forests and native vegetation,” says Peng.

“Satellite imagery gives us the knowledge to better understand soy supplier farms’ sustainability profiles and to do targeted engagement with producers on concrete ways to support them towards conversion-free production and expansion.”